thoughts on the thought daughter

literary it girls; thought daughters; and the commodification of self.

Recently I fell down a rabbit hole on Substack regarding the Joan Didion-quoting-cursive-writing-wired-earphones-wearing-male-gaze-appealing lit girl. For those who aren’t chronically online like me, lit girls refers to literary IT girls, or the “thought daughter”.

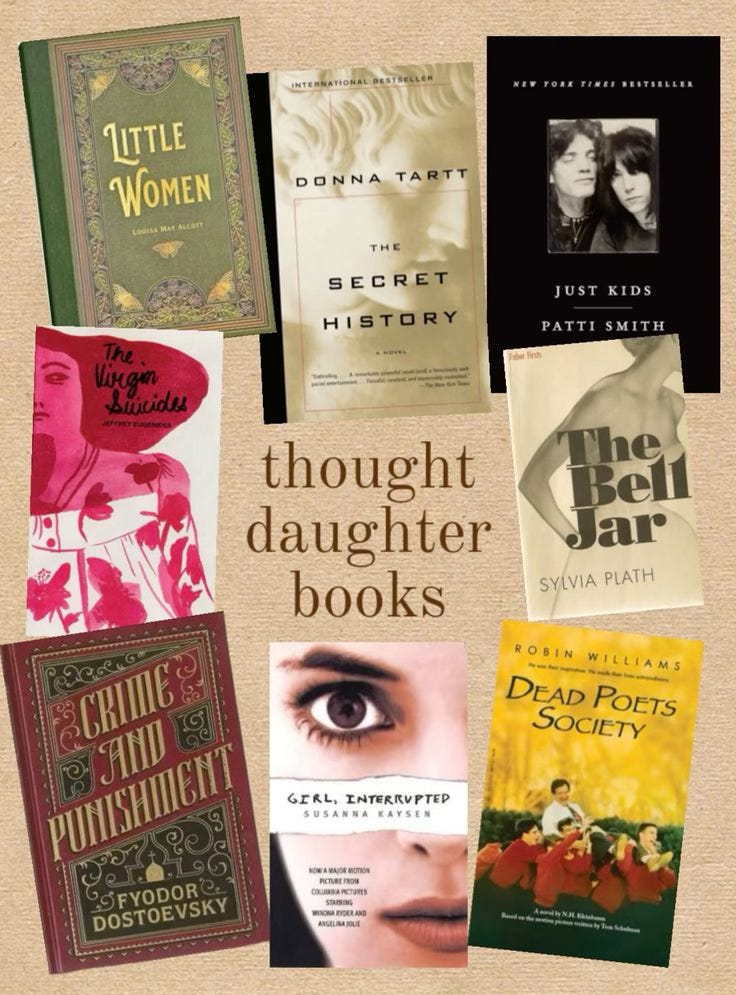

What initially started as a joke response to the “gay son or thot daughter” question, the “thought daughter” has assumed it’s own cool, blasé, and completely unpretentious identity. She reads serious books (re: the bell jar); she listens to cool music (re: lana del rey); she does not have any other hobby except for writing (re: journalling); and most importantly, she’s an intellectual. So much so that she absolutely detests the “thought daughter” aesthetic, despite creating entire tiktok series centred around “thought daughter fashion” and “lit girl approved books” and “the commodification of girlhood”. Oh but it’s ironic, of course, no one is above condemning one thing but perpetuating it all the same — welcome to the era of personal branding, darling!

That’s exactly what it is. People expressed their fears about the rise of anti-intellectualism, and found a way that would possibly stop it AND get their followers count up, effectively killing two birds with one stone. To that I ask: to what end?

There is this idea that to be successful in any creative industry, you must be a master at marketing. Your social media has to be perfectly curated to your target audience, and there better not be a strand of hair out of place even when filming a “candid, vulnerable, moment that no one has seen” (unless you have adopted the Messy Girl aesthetic, then you get a pass). It is almost normalised, and somewhat expected, for a woman to be a Cool Girl first, and creative second. Ottessa Moshfegh enthusiasts. Rory Gilmore autumn. Eve Babitz enjoyers. Girl Geniuses. Girl Bloggers. Girl Writers. Girl Dinners. Girlhood. I-am-a-twenty-one-year-old-teenage-girl. Girl. Girl. Girl. It is as though “girl” has transcended identity and mutated into a form of aesthetic for someone to put on and shed off whenever they feel like.

To clarify: I am not above any of this. I’ve made my fair share of “I’m just a girl” jokes, and I routinely stalk my favourite writers to see what they’re wearing, what they’re reading, what they’re eating, what they’re smoking, what they’re breathing. After all, we all want to be The Literary IT Girl. We all strive to have indie magazines personally reach out to us with a promise of endless publishing deals. We all dream of financial freedom packaged in a brown paper bag with a red lace ribbon. We all hope that one day, either out of luck or by being cool enough, one of our works would garner a million reads and catapult us into the realm of literary gods, leaving behind a legacy larger than what we could ever imagine. At its root, the thought daughter stems from young women wanting to be seen and praised for their intellectualism. At its core, the thought daughter stems from young women wanting their dreams to come true, but having to trivialise their dreams into a trending niche to make it digestible and desirable for rapid algorithms. As Helena Aeberli put it in her electrifying essay ‘in search of cool’:

We have to market ourselves, package ourselves into corners of the internet and carefully cultivate our social medias. We have to learn SEO, play into the algorithm, know the right tags to use, the right time to post. We can’t just strive to be writers, we have to strive to be literary it girls too.

It is no longer enough to be talented. It is now required for you to find ways to make yourself consumable, then allow people to have access to all “filtered” parts of you, whether you want it or not. The warped perception that we have of female creatives to be a guidebook into how to live by peering into their lives rather than their art has given us all a sense of entitlement. We idolise the introspective (the Sylvia Plath readers), and loathe those who aren’t (the Colleen Hoover readers); not realising that on both ends are women trying to fit into the molds created as a result of capitalistic-driven misogyny. The lit girl is not the answer to anti-intellectualism, but she is also neither the hero nor the villain.

I think of the fact that there exists a million and one archetypes for women to categorise themselves as: the thought daughter, the trad wife, the tomato girls, the pilates princesses, the coastal granddaughters, the mob wives, the clean girls — but why aren’t there any for men? At the end of the day, we are all finding ways to be palatable for the masses. These archetypes aren’t for us to discover our inner identity, they exist simply to make us marketable.

In turn, what will happen when the internet turns on micro-individuality and the commodification of self? What would we identify as then?